Author: C.S.R. Calloway

The Amusement Park

Life is much more than a mere roller coaster. As depicted in John Carpenter Presents George A. Romero’s The Amusement Park, it’s a whole carnival, and not one where you can escape the horrors of life, but one where you’re forced to face them head-on.

In June of 1975, George A. Romero premiered his psychological horror film The Amusement Park at the American Film Festival. The film was commissioned by the Lutheran Service Society of Western Pennsylvania, and serves as the only film Romero made as a work-for-hire project. That background perhaps explains why the film never received a major release until 2021, and why the story presented within this graphic novel is not as recognized in the pop culture zeitgeist as his Living Dead series and Tales of the Darkside. That unfamiliarity works in this adaptation’s favor, as every page brings an unexpected pivot on this terrifying ride.

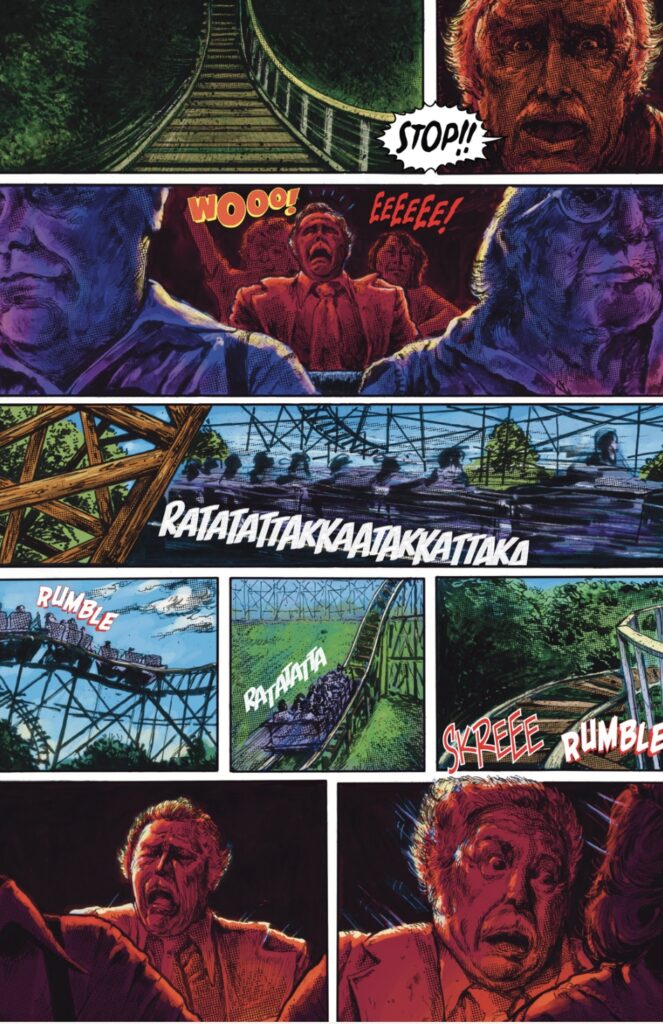

The narrative follows an elderly man who leaves a nondescript white room to explore “outside,” which, in this case, is presented as an amusement park full of rides and attractions, payable with tickets that can be bought with valuable items, though cash is preferred. The vague nature of the white room and the park creates an atmosphere of uncertainty and growing tension. Who is this man? How did he get here? And what does this place have to show him?

The answer, and the mini-odessey of getting that answer, is uncomfortable. What ensues during this man’s time in the park is a metaphor for the forced slide into marginalization. The man is increasingly made aware of his less-than-desired age, which is used to demean him, dismiss him, dehumanize him, and eventually take advantage of him.

Ryan Carr’s artwork effectively tracks the oscillating gloom of the man’s journey through the park, with vibrant expressions and claustrophobic angles. Without having seen the film from which the graphic novel was adapted, I cannot assess how effectively it replicates the cinematic version. Still, it does a fine job of presenting the allegory in this medium. Jeff Whitehead’s adaptation of Wally Cook’s screenplay is focused and tragic.

My one major critique is that the focus on a white male protagonist, implied to have a beneficial amount of wealth (in one stand-out episode, great significance is placed on the fact that the protagonist had enough tickets to dine in an establishment where the only other depicted customer is a rich man), gives the story an air of conditional tragedy. I thought of Martin Niemöller’s “First They Came,” specifically in that there is a sense that U.S. society treats the elderly in horrifying ways only because of how those injustices can reach even a person who previously had a modicum of privilege. Many of the injustices the central character faces will be familiar to women who have traversed male-dominated environments, or anyone who has been minoritized or marginalized away from the chosen majority of white, male, cisgender, and/or straight identities. In 1975, however, this story would likely have impacted an audience of that era with different media concessions than we have today.

Additionally, the framing device diluted the overall storyline and raised more questions than answered, though that could be collateral damage from its nature as an adaptation. Some things that work well in one medium don’t work well in another.

Overall, The Amusement Park was refreshing as a different type of horror experience from one of the titans of the genre, and I feel that Carpenter, Carr, and Whitehead have created an effective piece of work that stands on its own with the bonus of drawing more eyes to the original film.